“Full of brilliant, fun young people. Hope renewed for the future.”

Summary

Civic Future’s third annual summit, The Start-Up Society, brought together 160 leading thinkers, policy professionals, politicians, and academics to explore the future of governance, economic dynamism, and state capacity in Britain.

Hosted over two days at Latimer House in Buckinghamshire, the summit aimed to answer: How do we accelerate innovation, reform, and excellence in British institutions?

Our opening panel on Thursday evening explored how start-up principles might be applied to government and public institutions, in an era where bureaucratic sclerosis and administrative inertia are seen as key obstacles to reform. Tyler Cowen opened with a bold message: despite the prevailing sense of stagnation, we are living through a moment of immense opportunity, driven in part by rapid advances in artificial intelligence and a renewed appetite for institutional disruption. Andrew Greenway, drawing on his experience as a senior civil servant, warned that while start-up style reform is possible, success depends on political backing and a willingness to clear space within the system, not just layering innovation on top. And Ruxandra Teslo, approaching from a scientific and cultural angle, suggested that the real obstacle to reform is not bad intentions but a culture of agreeableness, risk-aversion, and unaccountable processes. The panel converged on the idea that meaningful reform requires not just better policy but a revaluation of courage, accountability, and disruption within state institutions.

Friday morning opened with a panel that tackled the question of why Britain is no longer growing, identifying a range of institutional, regulatory, and structural failures. Sam Bowman argued that the UK’s stagnation stems from broken feedback loops in decision-making, where regulators and local authorities face no consequences for blocking growth-driving projects like nuclear power stations and data centres. Mark McVitie pointed to dysfunction in Westminster and Whitehall, describing a political system designed to avoid risk and responsibility, and a media environment that rewards short-termism. Rian Whitton offered a longer historical view, suggesting Britain’s material economy has shrunk over the past two decades due to poor infrastructure policy, misguided net zero strategies, and global distortions from Chinese overproduction. All three panellists emphasised the need to reconnect local incentives with national priorities – whether through radical planning reform, automation subsidies, or fiscal decentralisation – to re-establish the conditions for sustained economic growth.

Next, Rachel Wolf and Emily Lawson discussed the challenges of reforming public services, drawing on their experiences in education and the NHS. Wolf spoke about her role in launching the free schools programme, arguing that new institutions were often better at driving improvement. Lawson, by contrast, focused on the need to fix what already exists, stressing that starting from scratch can cause disruption and delay. They explored why the same ideas, like autonomy and choice, worked in schools but failed in healthcare and agreed that real progress depends on picking clear priorities and sticking to them. Lawson also reflected on the COVID-19 response, noting that what made it work was a strong sense of purpose and people across different organisations working together to get things done quickly.

The panel on scaling start-ups explored the structural barriers facing ambitious businesses in the UK. Alan Chang highlighted the burden of excessive regulation, especially in energy and finance, arguing that complex planning rules and slow licensing regimes stifle innovation. James Wise rejected the idea that Britain lacks ambitious founders, instead pointing to a society-wide disincentive to take risks, from difficulty accessing finance to a lack of institutional support for entrepreneurship. Both praised Revolut’s global success but stressed that it was achieved despite the system, not because of it. The panel criticised the UK’s inconsistent regulatory environment, burdensome taxes, and lack of domestic growth capital, particularly for deep tech. While consumer demand and tech adoption in the UK remain strong, the speakers warned that high costs, crime, and poor public services are prompting talented entrepreneurs to leave. There was agreement that planning reform is critical, and that meaningful change will require both reducing barriers and shifting national incentives to reward those who build.

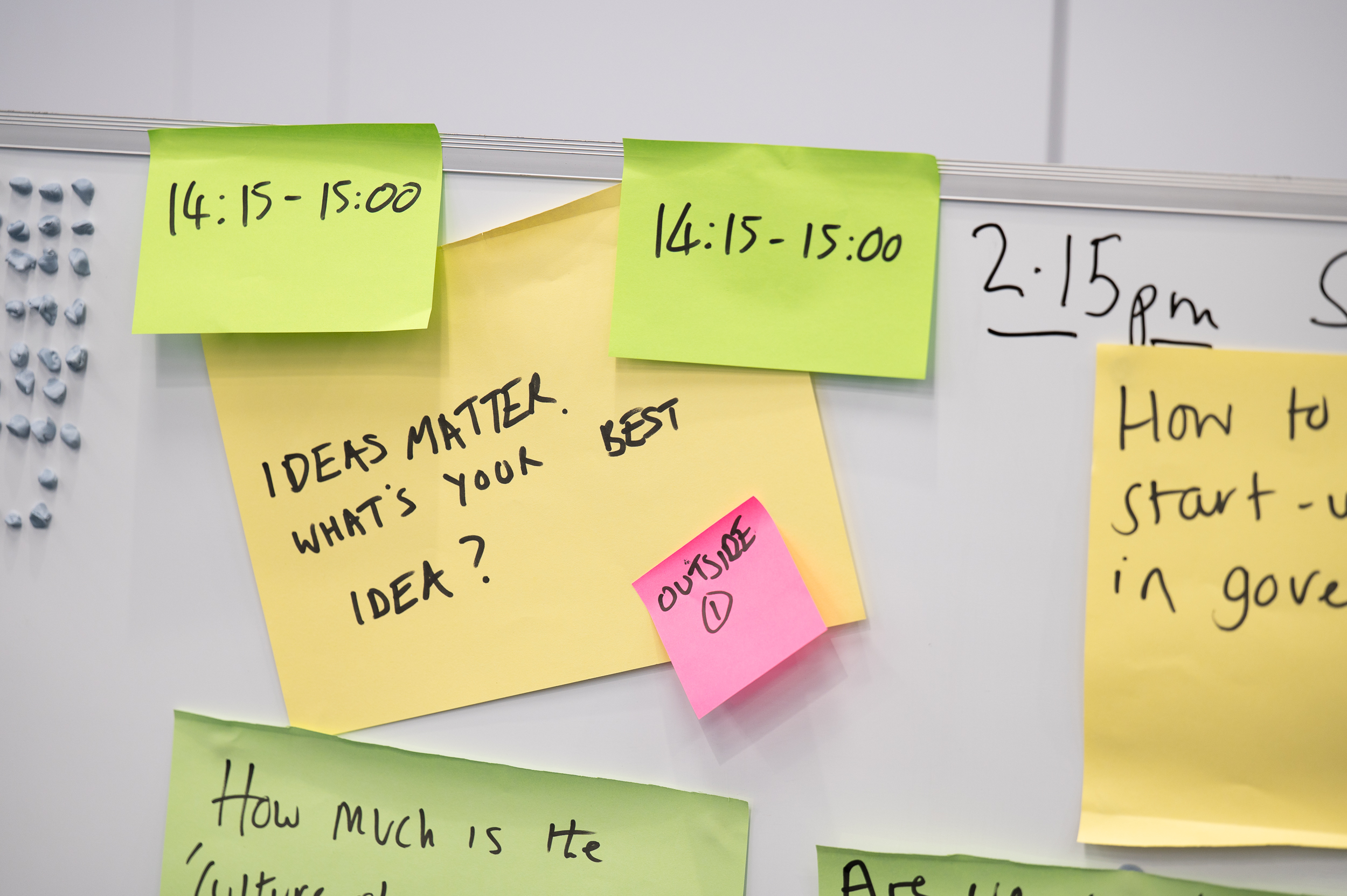

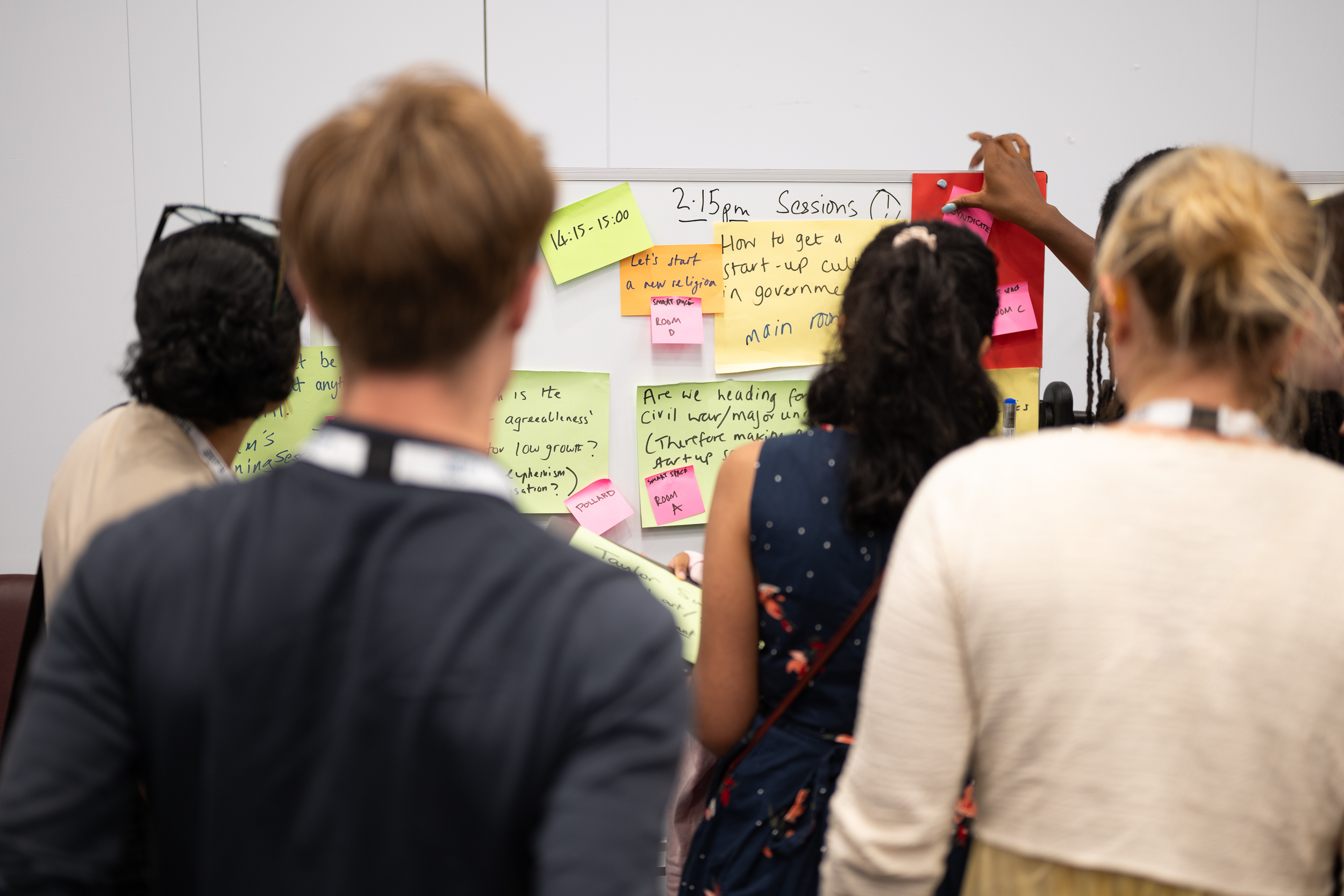

The post-lunch slot on Friday was reserved for unconference sessions, with participants leading talks on a wide range of topics including:

- We Are All Eastern European Now.

- Ideas Matter: What’s Your Best Idea?

- Is the “Culture of Agreeableness” Slowing Growth?

- Are We Heading for Civil Unrest?

- Let’s Start a New Religion

- Taylor Swift (and AI Ex-Girlfriends)

- We Shouldn’t Be Talking About Anything but AI

- Metapolicy and Theories of Statecraft

Delegates then reassembled for the penultimate session, an interactive workshop exploring the long-term societal implications of artificial intelligence. Marc Warner invited participants to consider different possible futures, asking them to reflect on a central thought experiment: what if the human brain is not uniquely special, but a kind of technology that AI could eventually match? He contrasted this with the more common view that AI will remain a subordinate tool, arguing that our assumptions about the brain shape how seriously we take the risks and opportunities ahead. Drawing on current trends, Warner showed how rapidly AI capabilities are advancing, suggesting that within a decade AI could perform highly complex tasks with near-human accuracy. The discussion ranged from labour markets and innovation to democratic accountability and values, with Warner emphasising that society is not yet thinking at the necessary scale or urgency. Rather than offering a single vision of the future, the session encouraged open-ended reflection on what AI might mean and how we might prepare.

And then the Summit was brought to a close with a session that explored the nature of political disruption through the lens of Brexit, with Tom McTague and Michael Gove offering perspectives on how fringe movements can challenge and ultimately overturn political consensus. McTague traced the deep historical roots of British Euroscepticism, arguing that Brexit was not inevitable but rather the result of persistent efforts by individuals once considered marginal. Gove reflected on his personal journey from early scepticism to front-line government, citing frustration with unaccountable EU decision-making as a radicalising force. Both emphasised that disruption depends not only on structural conditions but on intellectual rigour, strategic patience, and a willingness to challenge prevailing orthodoxies. The discussion also considered whether Brexit has delivered meaningful sovereignty or simply exposed new constraints. The session closed with reflections on how future disruptors across the political spectrum might reshape institutions through persistence, curiosity, and principled argument.

“An inspiring combination of some of the most interesting, thoughtful and impressive people working to improve the country.”

“Very high quality of attendees, with senior people feeling free to speak openly and frankly.”

“I thoroughly enjoyed it and even had a good idea for a socially geared start-up of my own on the motorway journey home!”

Photo Gallery